The case for decency

Don and Patricia Edgar

August 21, 2011

OPINION

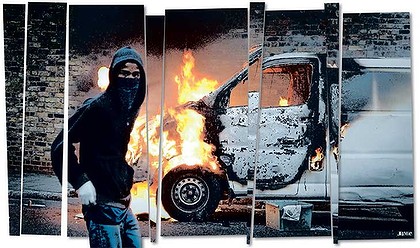

Original image of London riots by Getty

Our fractured society desperately needs to return to self-discipline and morality.

THE social and economic disintegration we are experiencing has a common core. The rioting in the UK; the corrupt financial system; politicians who lie about going to war, rort the system, pursue power in a media sideshow; a toxic news-gathering culture where police, detectives, journalists and their bosses collude - all are connected.

Harvard University's professor of cognition and education, Howard Gardner, in his latest book Truth, Beauty and Goodness Reframed, argues these cornerstones of society are under threat and must be reclaimed for us to survive. Gardner's critique of IQ tests led to an understanding that every child develops multiple intelligences, not simply verbal and mathematical skills. In particular, they must develop ''emotional intelligence'', a combination of insight/self-control and empathy. What the world needs now is more emotional intelligence and an ethical base for intelligent behaviour.

Gardner describes two broad types of goodness. ''Neighbourly morality'', which revolves around the golden rule of ''do unto others'', and cultural variations on the Ten Commandments (don't kill, steal, lie, cheat or freeload; honour your parents). Children need to learn this basic morality in the family and then apply it to people they relate to in everyday life. But the next step is harder to learn.

Because the world is wider than just family and friends, we all have to learn to respect the rights of strangers, to act responsibly, to behave morally towards others. And we do this through learning the ''ethics of roles'' - the rules that apply in school, in a footy match, in a job, where morality is not just about your own specific actions, but about codes of practice. We become ''the good team-player'', ''the good worker'' and ''the good citizen'', moving beyond self-interest.

The real test of ethics is responsibility. In a truly civilised society, professional codes of ethics regulate behaviour, ensuring we ask not simply what is good for me or my clan but what is good for all. In a bad society, self-interest rules and that is where we are living now.

A 17th-century proverb says a fish rots from the head down. The rot in the West is both bottom up and top down. Our young seem not to grow beyond a morality based on ego gratification because family and neighbourly socialisation has broken down and consumerism feeds our self-indulgence. Parents abdicate responsibility to hold their children even to a neighbourly morality.

Teachers are told they can't enforce standards of conduct or performance, they must preserve every child's self-esteem instead of rewarding excellence and effort. And the ethics of responsible work are no longer being modelled by business or political leaders because market forces fail to engender a sense of responsibility for the common good.

Teenagers naturally begin to be sceptical about their future. Gardner's research shows some alarming trends. Young workers seem to lack an ethical compass. Two-thirds of them admit to having cheated in class; a third have stolen from a store. Many want to cut corners at work, to take a pass from ethical work behaviour so they can gain success first. Small wonder London kids steal shop-front goods ''because the boutique makes too much money'', or justify criminal actions because ''the government lies all the time''.

These attitudes seem to derive from post-modernist thought, where all truth is seen as relative, standards are merely rules imposed on others, reflecting the power relations of our particular time. It's not just poverty or a denial of social welfare that is responsible. The old standards of religion, adult authority and professional behaviour have been undermined. Parents want to be their children's friends, not their guides and mentors. Schools are not articulating any future youth can envisage for themselves. The workplace no longer rewards effort; profit and exploitation rule. So why should a worker be loyal or care?

Youthful indifference also derives from the way the internet and new media blur the edges between mere opinion and established fact, creating, Gardner writes, ''a world of personas whose identity and roles we cannot trust''.

It's a world where journalistic rules are replaced by a culture of phone tapping and harassment, where institutions are driven by greed, sensationalism and profit; where corrupt bankers and financiers can be bailed out but ordinary citizens lose their homes.

An ethics based on market forces will not suffice, for ''where anything goes, nothing will endure''. There are standards of truth, goodness, fairness, justice, excellence and expertise; they must be restored for democracy to function.

The simplistic response of politicians and police to stamp out rebellion and deter others by harsh sentencing is just a first step. We then have to reassert the role of parents and other community members in setting standards, to act as models of the good citizen and the good worker.

Companies with practical work-family balance programs help the whole community cope with life's demands. Parents who participate in local affairs set a good example. Schools must engage every child, to ensure equal exposure to the skills of competent and responsible citizenship. The new media offer appealing opportunities for learning that we have not had before.

Workplace exploitation must end. Germany's social compact is one model. Instead of laying off workers, companies cut back working hours then used money set aside during good times to pay the workers about 60 per cent of their lost wages.

The Harvard Business School, which has shaped corporate culture worldwide, and bears heavy responsibility for the global financial meltdown, has a new dean, Nitin Nohria. He has been promoting business ethics. It's a welcome signal to the business world, where greed and disregard for people in the workplace is now endemic.

And we have to demand politicians conduct themselves as elected officials should, and focus on the common good, avoiding expediency and grandstanding in favour of ethical, humane, responsible policies for the future.

In the words of Benjamin Franklin: ''We must indeed all hang together, or, most assuredly, we shall all hang separately.''

Don Edgar and Patricia Edgar are sociologists. Don was founding director of the Institute of Family Studies. Patricia was founding director of the Australian Children's Television Foundation.

patriciaedgaranddonedgar.com